What is an auteur? Originating from the French New Wave of the 1940s, the term "auteur" describes a movie director who has a very distinct and specific style of filmmaking.

They tend to have complete creative control over their films, which is evident when you can instantly tell who made a film just by watching it unfold on screen. For example, Quentin Tarantino's signature style involves bloodshed, racism, and sharply written dialogue.

Auteur filmmakers often gravitate toward the same cast and crew, and they often play with the same themes and aesthetics.

Here are some of the most famous movie directors and what their cinematic styles involve, including everything from narrative tropes to camera shot types to color grading in post.

22. David Fincher

David Fincher's movies tend to bite of dreary realism. The urban settings are colored in grays and browns to paint locations where modern-day horrors often unfold.

Fincher has used these dull tones to reflect the monotonous lifestyle of capitalist consumerism in Fight Club, as well as the dark nature of the Zodiac murders in Zodiac.

Rainy streets and brown suits litter Fincher's worlds, characterized by themes of murder, social alienation, and psychological torment. His meticulous and perfectionist approach to filmmaking makes Fincher's work extremely detailed and immersive.

Dialogue plays a huge part of Fincher's filmography, with long exposition scenes carefully crafted and performed. The Social Network, with its built-up back-and-forth conversations, is one of the best examples of this.

Fincher also loves the split-comping technique (also called the invisible split-screen technique), the use of flashbacks, and character-centric plot twists. Gone Girl, Se7en, and Fight Club all had viewers gasping in shock at Fincher's big reveals.

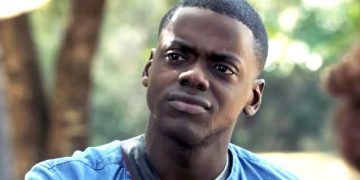

21. Danny Boyle

Danny Boyle made his claim to fame with Trainspotting, the 1996 dark comedy about heroin addicts. Trainspotting laid the groundwork for Boyle's signature use of POV shots and surreal sequences.

With its drug-addicted protagonist, Trainspotting has many bizarre scenes, like a baby crawling on the ceiling, or Mark Renton climbing through the grossest toilet in the world and into the ocean. We see this again later in the kaleidoscopic scenes from The Beach and 127 Hours.

Boyle is an auteur with edge, using choppy and fractured editing to mirror his characters' fragmented mental states (whether because they're drugged, starved, or self-mutilated).

If you're a fan of fast-paced movies, Danny Boyle is the director you should check out. His films are rarely static, jumping from one extreme to the next and merging dreamscapes with reality while popping with colors. And don't forget the voice-over narrations!

20. David Lynch

If you thought Stanley Kubrick was weird, try stepping into the world and filmography of David Lynch. The director uses transcendental meditation (as explained in interviews) to get ideas and inspiration for the dreamlike sequences in his films.

Not that his movies are fantasy, per se; they're more like twisted, nightmarish versions of reality. Time zones blur, dreams can cross into day, and nothing is quite as it seems—his uncanny aesthetic is most obvious in Eraserhead and Blue Velvet.

There's something purposefully off about Lynch's films—something you can't quite put your finger on, yet can't take your eyes off of.

Lynch uses lots of atmospheric music and cross-fades to create his ambience. The constant background noises are haunting and hypnotic, drawing you into his world of obsession, murder, and deceit.

His films are essentially surrealist paintings come to life. A modern moving Salvador Dali, if you will.

19. Woody Allen

Woody Allen's films are like a leisurely stroll in the park. The narrative meanders along at its own pace, following the loose threads of casual conversations. They mostly center on domesticated themes, like relationships and pop culture, starring privileged white characters.

One of those characters is often played by Allen himself, who starred in Annie Hall as well as Hannah and Her Sisters. Allen maintains a certain on-screen persona in his movies: the nervous-yet-witty intellectual.

Timothée Chalamet's appearance in A Rainy Day in New York is eerily Allen-esque, chatting and stumbling around the screen neurotically like a young version of the director.

Woody Allen's movies also tend to be sarcastic, stuffed full of inter-textual references and cynical observations.

Moreover, Woody Allen has a love for big cities—Paris, New York, Rome, etc. He loves the hustle and bustle of city life, the romance of rain, and lots of nostalgia.

The stories of love, youth, identity, and art in these settings are far removed from the grit and adventure of blockbusters. And while Allen's films are often small in scope, they're grounded in reality and highly entertaining and easy to relate to.

18. Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen is an esteemed British filmmaker who, despite only having a few movies in his canon compared to most auteurs, has already managed to nab a CBE and an Oscar.

Thematically, McQueen deals with minority groups and marginalized voices. This was first established with his 2008 biopic Hunger, centering on Irish republican prisoners on hunger strike in 1981.

McQueen then covered black history in 12 Years a Slave (2012) and the Small Axe anthology (2020), which was made in support of Black Lives Matter. The sex-addicted protagonist of Shame (2011) could arguably be included as a marginalized character, too.

One thing that marries all of his films together is the use of the long take, which is apparently McQueen's favorite shot.

Whether it's Chiwetel Ejiofor dangling for an uncomfortably long time in a noose in 12 Years a Slave or the 28-minute-long two-shot in Hunger, McQueen knows how to hold our attention without any cuts!

17. John Ford

John Ford, the King of the Western. He directed over 140 films and none of them seemed to decline in quality compared to the last.

Ford single-handedly defined the Western Frontier on the big screen, harking back to Frederic Remington's cowboy paintings. His on-location shooting made space for panoramic wide shots, letting the camera soak up all the expansive desert plains.

Ford created postcard pictures of the American West, which all began with the 1939 classic Stagecoach. Whether in black-and-white or color, the atmosphere of the Wild West is always vividly captured in Ford's work.

Movies like My Darling Clementine (1946), Rio Grande (1950), and The Searchers (1956) went on to influence the Western genre forever.

Ford returned many times to film in Monument Valley, and even when he did shoot on-set, Ford ensured elaborate Californian ranches were built to embody the B-Western. Ford's abundance of non-Western films were equally expressionistic and light on camera movements.

16. Spike Lee

"A Spike Lee Joint" is how this director always opens his movies, which he's never fully explained but we still love anyway.

Spike Lee is such an auteur that there's even a name for his cinematic style: "Spikeism." It entails a lot of bright, popping colors and visual cues that draw your attention to the artistry in front of you.

Some great examples of this include the highlighting of faces in the crowds of BlacKkKlansman (2018) and the primary-colored clothing and gold jewelry in Do the Right Thing (1989).

Most of Lee's characters live in urban landscapes that he injects with personality, as if the settings were characters unto themselves.

His settings are usually New York, as it was in She's Gotta Have It (1986), Crooklyn (1994), Clockers (1995), He Got Game (1998), 25th Hour (2002), and Do the Right Thing (1989).

Beyond the setting and look of his films, Spike Lee focuses on themes of race relations, politics, poverty, and the black community through an insightful blend of pathos and humor.

15. Tim Burton

Tim Burton is the master of gothic-infused cinema. Skeletal protagonists and sunken eyes often mark his claymation movies, which are unique sights to behold.

His desaturated animated fantasy worlds populated by ghosts and ghouls make for excellent family entertainment—all the way from The Nightmare Before Christmas to Corpse Bride.

His live-action movies are just as brilliantly gothic, and they often star Johnny Depp and/or Helena Bonham Carter.

Edward Scissorhands sees a pasty-white, scarred protagonist in a black-buckle outfit and literal scissors for hands. Dark Shadows stars a vampire in a black cape and long fingernails. Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street is led by a murderous barber with a streak of white through his frizzy black hair.

All of these spooky-looking, utterly Burton-esque protagonists are played by Johnny Depp to perfeciton.

None of Burton's characters seem to have ever caught sun in their lives. Their skin is as white as bleached sheets, and they're often surrounded by rain and fog. Burton's films are full of dark atmospheres that are perfect for Halloween.

14. Terrence Malick

Terrence Malick has a particular way of capturing the abundance of our world's beauty and the grandness of simplicity.

His filmography is dotted with poetic epics, from The Tree of Life (2011) to A Hidden Life (2019). Notice how both of these films are centered on "life"—in all its stunning, tragic, wonderous ways.

The Tree of Life literally takes us through the birth of the universe, starting in space and through the dinosaur age, then the 1950s, and then modern day. Malick views the mundane in a spiritual, philosophical light with free-roaming cameras that relay the magnitude of nature.

He also achieves these extraordinary visions through unconventional means. For example, Malick loves improv. He often gives his actors reading lists alongside (or instead of) scripts, and he isn't afraid to leave half of his footage on the cutting room floor.

Terrence Malick's bold methods are what allow for such bold storytelling, from Badlands (1973) to The Thin Red Line (1998).

13. James Cameron

James Cameron isn't intimidated by the epic scope of his projects. The most obvious example is Titanic (1997), the now-infamous disaster film that was once the most expensive movie ever made.

As film technology wasn't as advanced back then as it is today, the production of Titanic was a hellish feat that went 138 days over schedule. Like Titanic, Avatar was also a big-budget blockbuster—even if viewers weren't as impressed as they were with a capsizing boat.

The Canadian filmmaker is known for making the most of SFX, pioneering all kinds of technological advancements in the movie industry, and breaking all kinds of records. (As of this writing, James Cameron created three of the five highest-grossing movies of all time!)

Most of Cameron's film canon falls in the realm of sci-fi (The Terminator), fantasy (Avatar), and action-adventure (Aliens).

12. Denis Villeneuve

Denis Villeneuve is a man who has curated his own cinematic language of a sort, often relying on noir-like imagery and smoky cinematography that flows naturally into a complete masterpiece.

He's done this in Dune (2021), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), and Arrival (2016). The futuristic, alien settings of these films are never presented to us in the usual Hollywood space-flick way. Instead, Villeneuve treats every frame like a painting—precise, opulent, and symbolic.

The satisfyingly symmetrical, neon-lit frames in Blade Runner 2049 add a new dimension to the urban cyberpunk vibe that Ridley Scott first laid down in the original Blade Runner (1982). Arrival doesn't feature any green, googly-eyed aliens, but inky limbs billowing in the mist.

Everything about Denis Villeneuve is sleek and professional, and his films always feature strong performances. Even when he steps away from sci-fi, he maintains his stylish depth—as he did in Prisoners (2013).

11. Quentin Tarantino

The fake-blood budget for Quentin Tarantino's films must be extortionate. This movie director loves violence—especially during the his movies' grand finales.

And yet, Tarantino's goring final battles are often preceded by lots of heavy and cursory dialogue. Some of these conversations get so tense you'll find yourself physically holding your breath.

In fact, Tarantino's mastery of tension through dialogue is one of his best triats. Take, for example, the opening to Inglorious Basterds, which is analyzed by film students the world over.

Christoph Waltz plays a Nazi officer who enters a French farm—one where a Jewish family is hiding beneath the floorboards. Waltz's unreadable smile makes it unclear if he knows about the family, and you could cut the tension in that farm with a knife.

Following this, of course, is a shootout. Tarantino often swings between taut silent atmospheres and explosive action sequences in this way. Get used to it.

Tarantino's characters often have excessively detailed conversations—typically in a restaurants, diners, and cafes—sometimes about nothing in particular. In Reservoir Dogs, there's an entire scene where the diamond thieves discuss the pros and cons of tipping culture.

Here are a few key themes to look out for in a Tarantino film: crime, money, death, humor, and revenge.

Some of his favorite camera techniques are POV shots from the trunk of a car, tracking shots, and birds-eye views. He loves to use flashes of black-and-white (particularly in the Kill Bill movies) as well as dance routines and Mexican stand-offs.

10. Ridley Scott

Before Ridley Scott carved out a fresh look for dystopian films with Blade Runner, he solidified his name in the sci-fi genre with Alien (1979).

It's well known that Alien changed film history forever, striking the perfect balance between sci-fi and horror, drawing us in with its iconically chilling tagline: "In space, no one can hear you scream."

Although James Cameron stood on the shoulders of Alien's success when he made Aliens, it never came close to matching the first film's ability to capture the truly empty void of space. There are no crowded galaxies or planet populations in Alien—just pitch black (and the alien).

Conversely, Blade Runner is stuffed head-to-toe with people, buildings, and lights. Yet, even so, a feeling of loneliness is created from its isolated characters trudging through the perpetual night-time.

All of this points to Ridley Scott's keen eye for production details, giving viewers a feel for the textures and emotions of his lonely worlds—which include gangsters (American Gangster), swordfighters (Kingdom of Heaven), and historical dramas (Gladiator).

9. Alfonso Cuarón

Most cinephiles agree that Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) is the best of the Harry Potter movies. Why? Because Alfonso Cuarón directed it, of course!

The third installment marked a clear shift in tone for the series, from children's wizarding fun to seriously dark and evil forces.

Cuarón brought a lot of maturity to the franchise (which helped to keep adult viewers hooked) by drawing on the success of his Mexican road drama Y Tu Mamá También three years earlier.

Symbolism, intentional lighting, and characters that go beyond simple good-versus-bad are some of the key trademarks found in The Prisoner of Azkaban—and the rest of Cuarón's incredible filmography.

And then there's Children of Men (2006), which could easily be considered his greatest movie ever made.

Children of Men is littered with religious motifs—the pregnant Kee reminiscent of the Virgin Mary, copying the pose found in The Birth of Venus, a mother cradling her dead son like Christ in The Pietà—that match his usual dark, grungy atmosphere.

8. Francis Ford Coppola

Francis Ford Coppola is the name behind two of cinema's greatest modern treasures: The Godfather Trilogy (1972–1990) and Apocalypse Now (1979).

This New Hollywood director was at his height during the 1970s, joining the ranks with Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, and Brian De Palma.

Coppola's characters reject a black-and-white view of morality, with a heavy focus on family—or lack thereof—and themes of paranoia.

Indeed, The Conversation (1974) encapsulated the essence of paranoia, with a protagonist who's literally a surveillance expert obsessed with listening in on people and their plots. It even opens with a long take that mimics binoculars and spycams!

Although Coppola's films have ambitious runtimes and epic productions, his camerawork is fairly simplistic: long takes, tracking shots, slow zooms, still close-ups, etc. These often build up to a big crescendo, like when Michael shoots Sollozzo in The Godfather.

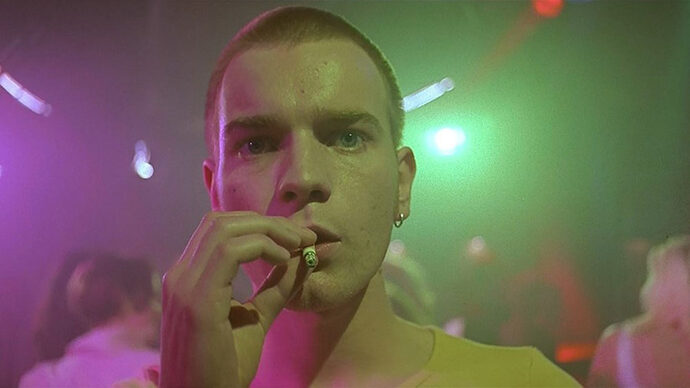

7. Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick is most recognizable for his use of symmetry. There's usually a clear horizon cutting across the screen, and everything is organized cleanly—precisely—within the frame.

Kubrick's frequent employment of the one-point perspective has produced some iconic shots, such as the hallway of the hotel in The Shining or the above image from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Kubrick has directed several landmark films, and these films often include bravely long (and bizarre) takes. Kubrick never took the shortcut for anything, with most of his films spanning epic runtimes that had to be cut down for theaters.

Thematically, Kubrick teeters on the strange and the perverse. A Clockwork Orange is famously controversial, and was even banned in Britain after it inspired a string of copycat crimes.

Traumatized characters, insane killers, erotic cults, and evil computers make for a very dark filmography. That said, they're carefully constructed masterpieces worth watching nonetheless.

6. Christopher Nolan

Christopher Nolan loves to mess with your mind—especially through the manipulation of time. And we aren't just talking standard back-and-forth time travel. No, that'd be too easy for Nolan.

His fascination with temporal concepts can be found starting in his earliest work, where the protagonist of Memento covers his body in messages for himself because he suffers from anterograde amnesia.

Furthermore, planets (and dimensions) run at different rates in Interstellar while time inverts on itself in Tenet. Like the title Tenet itself, time is the same forwards as it is backwards in Nolan's most recent mind-bending thriller.

And when Nolan isn't playing with time, he's playing with space. Walls bend and gravity shifts in Inception, where characters can enter and control their dreams.

There's a lot of globe-trotting across Nolan's films, who likes to seek out vast and expansive locations for his epic-scale stories. They tend to be action movies grounded in drama—like the emotional wartime toil of Dunkirk or the father-daughter relationship in Interstellar.

As far as appearance, Nolan's films are generally modern and sleek. The color palettes are dominated by cool tones of silver and grey—cityscapes and expensive cars and Batman's underground garage.

Nolan also has a signature sound design, which often involves a deeply thumping buildup of sci-fi-inspired sounds. If you ever see his movies in IMAX (which we suggest you do!), you can feel the visceral music literally vibrating through your body.

For better or worse, Christopher Nolan's movies are always must-watch because they're more than just films. They're experiences.

5. Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson is one of the most obvious auteurs that come to mind when anyone talks about iconic movie directors with style. He's the king of "Indiewood," merging independent art cinema with mainstream Hollywood.

Visually, his trademarks are symmetrical shots, frame-within-a-frame, and coordinated mise-en-scene. For example, the all-yellow room in Hotel Chevalier and the pink hotel and bakery in The Grand Budapest Hotel. His movies are always bright and cheerfully color-graded—the complete opposite to someone like David Fincher.

Narratively, Wes Anderson focuses on dysfunctional family dynamics (especially father figures), child characters, and themes of death (handled in darkly comic manner).

There's a surrealist quality to his work, which marries upbeat characters with deadpan comedy and highly stylized cinematography.

Wes Anderson often opts for handmade props over realistic ones, adding a rustic home-movie feel to his polished masterpieces.

4. Guillermo del Toro

Guillermo del Toro is set apart from most other movie directors by his twisted sense of fantasy and his love for the supernatural. We're not talking about "mainstream kids"-type fantasy; we mean dark and morally ambiguous fantasy that symbolizes deeper truths.

Del Toro touches on the political and the religious; ghosts and strange animals; the innocent and the evil. He likes to explore huge and heavy ideas through his magical lenses, diluting his films' child-like qualities with more sinister topics like war, abuse, and death.

Doug Jones is a favorite casting choice for del Toro, although you wouldn't necessarily recognize him—because Jones is always decked out in creepy (albeit impressive and detailed) costumes. He's contorted his body as the Pale Man and Fauno in Pan's Labyrinth, and the Amphibian Man in The Shape of Water.

Del Toro's protagonists are usually outcasts with big hearts and troubled lives. He's curious about the underdogs, about nature, about love, decay, and true evil.

Green emerald hues tend to dominate Del Toro's color palette, undergirded by inky metallic tones of black and gray, which all unite to paint the mossy forests and Soviet labs of del Toro's landscapes.

Haunting Catholic imagery litters his work, and he isn't afraid to push the boundaries of what mainstream audiences will enjoy without getting too weirded out!

3. Paul Thomas Anderson

Paul Thomas Anderson is one of those rare directors whose films utterly exude confidence and craft.

He makes masterpieces look so easy, complete with perfectly sculpted scripts, flawless pacing, strong character development, dense dialogue, and lovely cinematography.

As if that weren't enough, his prestigious choice of actors—often working with Daniel Day-Lewis, Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John C. Reilly, and Philip Baker Hall—certainly doesn't hurt.

Paul Thomas Anderson's films tend to be period pieces, but not of the corsets and duels variety. We're talking hippies (Inherent Vice), the Western Frontier (There Will Be Blood), and the 1950s (Phantom Thread).

Anderson's most recent film, Licorice Pizza (2021), takes place in 1970s California with anti-heroic characters who navigate chaotic lives across an epic runtime. It earned him several Academy Award nominations.

2. Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock is one of the original auteurs of cinema. The legendary director was a meticulous artist who planned out detailed storyboards of every single frame in his movies.

Hitchcock's camera movements are precisely controlled and deliberate, masterfully using character blocking and tracking shots to present the screen like a chessboard of players.

Some of his frequent conventions include blonde female characters (and killing them off, which earned him a reputation for misogyny), birds (as evidenced in The Birds, Vertigo, and even Norman Bates stuffing birds in Psycho), and the motifs of police, crime, and murder.

Hitchcock was a pioneer of the thriller genre, giving birth to the slasher subgenre with the infamous shower scene in Psycho. Every filmmaking method, technique, and element of mise-en-scene is intentional.

For example, the in-your-face contrast of red and green in Vertigo deliberately signify Scott's love and dangerous obsession, and Madeleine's mythical uncanny presence. The two hues pop out of the screen, symbolically merging and crossing-over as the story unfolds.

Also, you know it's a Hitchcock film when Bernard Herrmann is on the score and Jimmy Stewart is the star among an array of less-than-heroic characters.

1. Akira Kurosawa

Akira Kurosawa is among the top five most influential filmmakers of all time. Although he was Japanese, Kurosawa's films are so reminiscent of Western movies that he helped propel the genre forward in America.

His narratives and visuals are strikingly grand, full of great Japanese empires, battles, samurais, axial cuts, and sweeping views. Every frame is like an opera stage of bloody violence and gorgeous natural backdrops.

Kurosawa's cause-and-effect, hero-driven narratives felt right at home with the films being made in the States at the time, but his fluid camera movements often broke the 180-degree axis rule that Hollywood clung to so tightly, causing the industry to reconsider.

Kurosawa had such a command of his craft that he even employed the cheesy "wipe" transition without it feeling cheap or unprofessional. He also paid immense attention to his soundtracks, but used them to counterpoint the scene's emotion rather than reinforce it.

These things should've been disastrous for him, but they helped make Akira Kurosawa the most legendary filmmaker in Japanese history. Some of his most notable works include Ran (1985), Seven Samurai (1954), Ikiru (1952), and Throne of Blood (1957).