Stanley Kubrick is one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in cinema history.

His extreme attention to detail earned him a reputation as a demanding perfectionist—so much so that he would force actors to repeat dozens of takes just so he could capture the exact performance he needed.

Elstree Studios claims that Kubrick shot more than 1.3 million feet of film on The Shining: about 120 takes for every shot used, compared to the usual 5 to 15 takes on a normal filmmaking production.

This obsessive need for perfection was clearly excessive, but it achieved spectacular results. It's hard to deny that Kubrick's methods worked, and he revolutionized cinema multiple times with the styles and techniques he pioneered.

Do you like trippy movies with symbolism-laden sci-fi journeys, crime-ridden futuristic dystopias plagued by sociopathic gangs, families enjoying extended stays in haunted luxury hotels, or hilarious military bloopers that threaten the existence of mankind?

Then you'll love Stanley Kubrick's filmography! Here's our ranking of the best Stanley Kubrick movies.

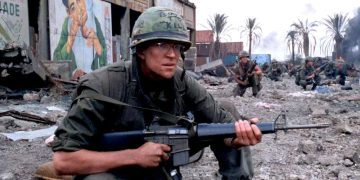

7. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Watching Full Metal Jacket is like watching two different movies stitched together, yet resulting in a satisfying whole.

The first half follows the main character Private Joker as he goes through Marine boot camp. The second half shows his experience in Vietnam around the time of the Tet Offensive.

If I were to judge the movie by it's first half, Full Metal Jacket would be much higher on this list—R. Lee Ermey's performance alone is incredible, and Vincent D'Onofrio's performance seals the deal. Yet while the first half is exceptional, the second half feels like just another Vietnam War movie.

The screenplay for Full Metal Jacket was adapted from the book The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford. Kubrick was attracted to the novel's "sense of uncompromising truth." He went on to say:

"The book offered no easy moral or political answers; it was neither pro-war nor anti-war. It seemed only concerned with the way things are. There is a tremendous economy of statement in the book, which I have tried to retain in the film."

One of the main themes of the film is the loss of innocence as a consequence of war—namely America's innocence, which is personified by Private Joker.

While undeniably an anti-war film, the message Kubrick was trying to get across was much more ambiguous than the more easily discernable moral intentions in his other movie, Paths of Glory.

He said about Full Metal Jacket:

"You shouldn't make a war film if all you have to say is, 'There should be no more wars.' Even the generals will agree with you about that, but it's not my job to say what it is. I try and put as much as I can into the film, to make the best film I'm capable of. But once we finish shooting, I'm probably the last person in the world who can tell you what the film is about."

6. Paths of Glory (1957)

Paths of Glory is a war epic and a courtroom drama rolled into one film. The story is set during WWI when the front lines of the French and German trenches had not changed even after two years of fighting.

Kirk Douglas plays a French Colonel who's put in charge of leading a doomed attack on the German line. The General commanding the attack is motivated purely by professional ambition. He's indifferent to the lives of his troops, and even orders an artillery to fire against his own men at one point.

During the attack, many of the troops refuse to obey the orders to charge out of the trenches to certain death. After the battle is lost, the French military decides to punish the disobedient troops by randomly picking three men from their ranks to execute.

Kirk Douglas' character volunteers to act as their defense during their trial. The three soldiers lose the trial and are executed by firing squad. Paths of Glory deserves its continued reputation as one of the most purely anti-war movies ever made.

It highlights the glaring hypocrisies of war and questions the motivations and decisions that condemn thousands to a meaningless death, all for the sake of self-serving individuals in power.

The glaring futility and stark horror of WWI trench warfare provided a perfect canvas for Kubrick to explore a theme that runs through many of his films: that powerful institutions are vulnerable to the threat of individual human ambition, weakness, and stupidity.

5. Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove is a dark comedy satire set during the Cold War about a psychotic American general who orders a nuclear attack on Russia.

In the beginning of the movie, a text disclaimer from the United States Air Force appears on the screen: "None of the characters in the film were based on real persons." Apparently, that wasn't true.

According to history professor Paul Boyer, the general played by Sterling Hayden was based on Curtis LeMay, the head of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) during the 1950s. LeMay commanded the operations that dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the firebombing of Tokyo during WWII. It was said he never met a bombing plan he didn't like.

Paul Boyer also claims that the character Dr. Strangelove is based on Wernher von Braun. Von Braun was a former Nazi scientist who was moved to the US during Operation Paperclip, then headed America's space research program after WWII. More people died in building his V-2 rockets for the Nazis than were killed by them as a weapon.

As absurd as Dr. Strangelove is as a movie, it's grounded in a reality that seems all too real and plausible. The Air Force's disclaimer at the beginning (that "their safeguards would prevent the occurrence of such events as are depicted in this film") reads like it's part of the joke.

Really, it fits the satirical tone of the movie quite perfectly. It's intended to reassure audiences, but within the context of the movie, it has the exact opposite yet comically dark effect.

4. Barry Lyndon (1975)

I know what you're thinking: "Not another Oscar-bait period piece where people in frilly costumes and powdered wigs gossip about crackers and silverware with goofy accents I can't understand! Those movies are the worst!"

You're not wrong. Those movies are the worst. But Barry Lyndon is different, because Barry Lyndon is one of a kind.

Adapted from Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. by William Makepeace Thackeray, the film follows the tragic life of the deeply flawed Irish rogue Redmond Barry of Ballybarry as he schemes and manipulates his way into the higher echelons of 18th century British society.

Kubrick's attention to detail is on display in Barry Lyndon. An extensive amount of research and preparation went into ensuring that everything looked authentic and stunning. In his own words:

"We studied every painter of the period, photographed every detail we could think of; bought real clothes of the period, which, incidentally, were almost invariably too small."

Around 250 soldiers from the Irish Army were involved in the full-scale battle reenactments of the Seven Years' War. They accurately portrayed the skirmishes and maneuvers of the time. Every costume was designed with the help of an expert historian in military uniforms.

All of this meticulous preparation resulted in scenes that almost look like moving paintings of the era. Kubrick's focus on using as much natural light as possible really pays off. If you can get past the stigma of this typically boring genre, then give Barry Lyndon a chance!

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

The first time you watch 2001: A Space Odyssey, you may be left scratching your head like an early hominid trying to comprehend a hauntingly perfect space obelisk that appeared out of nowhere.

You may start grabbing nearby objects and swinging them wildly in the air while barking in terrified frustration as you try to understand what this bizarre thing you've encountered is trying to tell you.

Don't worry. That happens to everyone on their first viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey. But come back for a second watch later—or maybe even ten rewatches—and you might start to be able to pretend you know what's going on.

2001: A Space Odyssey pioneered all kinds of filmmaking techniques that are still used to this day. The groundbreaking visuals that astounded audiences upon its release in 1968 still hold up. Even with the aid of CGI, modern movies struggle to achieve the splendor that Kubrick was able to accomplish with only practical effects.

But what is this weird long movie all about?

There seems to be an entire industry devoted to analyzing the meaning and symbolism of 2001: A Space Odyssey. But it was a 15-year-old New Jersey high school sophomore named Margaret Stackhouse whose interpretations earned the most praise from Kubrick.

Stackhouse's teacher sent her reflections on the movie to Kubrick, who remarked:

"Margaret Stackhouse's speculations on the film are perhaps the most intelligent that I've read anywhere, and I am, of course, including all the reviews and the articles that have appeared on the film and many hundreds of letters that I have received. What a first-rate intelligence."

Stackhouse's text is available online and is definitely worth the read for anyone who's interested in exploring the deeper interpretations of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

2. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

A Clockwork Orange stars Malcolm McDowell as Alex Delarge, one of the most contemptible characters ever put on screen. In the words of Stanley Kubrick, "Alex makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption and wickedness. He is the very personification of evil."

The movie begins with Alex and his gang (his "droogs") committing horrific crimes while intoxicated on milk spiked with drugs. Alex is then sent to prison for his violent debauchery...

...where he undergoes experimental psychological conditioning that results in him becoming physically ill whenever he encounters imagery or situations of a sexual or violent nature. In the end, the procedure is reversed and Alex is returned to being his old terrible self.

But one of the central questions asked by the movie is whether Alex was ever actually reformed in the first place. He had no choice over his actions and was reacting to an involuntary physical response. Right?

This controversial film was pulled from theaters in England by Stanley Kubrick himself in 1973 after a series of copycat crimes committed by droog lookalikes, and after receiving multiple threatening letters. A Clockwork Orange wasn't seen again in England until 2000.

Kubrick stands by his decision to create such a monster:

"It was absolutely necessary to give weight to Alex's brutality, otherwise I think there would be moral confusion with respect to what the government does to him. If he were a lesser villain, then one could say: 'Oh, yes, of course, he should not be given this psychological conditioning; it's all too horrible and he really wasn't that bad after all.'

On the other hand, when you have shown him committing such atrocious acts, and you still realize the immense evil on the part of the government in turning him into something less than human in order to make him good, then I think the essential moral idea of the book is clear.

It is necessary for man to have choice to be good or evil, even if he chooses evil. To deprive him of this choice is to make him something less than human—a clockwork orange."

1. The Shining (1980)

The Shining stars Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance, a struggling writer who takes a job as the winter caretaker of the Overlook Hotel in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. The job requires that he and his family live in the hotel, completely cut off from the outside world until the winter snow melts enough to make the only road passable again.

And, of course, the hotel is haunted. Or is it?

Stanley Kubrick and co-writer Diane Johnson put a lot of thought and attention into how the ghosts were portrayed in The Shining. Are they real? Or simply hallucinations brought on by mental disturbances? That's ultimately left open to interpretation.

But Johnson offered a third possible explanation:

"The psychological states of the characters can create real ghosts who have physical powers. If Henry VIII sees Anne Boleyn walking around the bloody tower, she's a real ghost, but she's also caused by his hatred."

Whatever the truth may be, if I find myself in the Overlook, I'm taking the stairs just in case. The possibility of a massive blood flood while trying to take the elevator doesn't seem worth the risk.