Tripping at the finishing line is one of the cruelest metaphors to describe a movie. It basically tells filmmakers that they came within striking distance of cinematic victory, only to lose it at the end.

On the flip side, you have those rare films that successfully capture—in truly beautiful ways—the essence of what the film strove for, from conception to completion. Filmmakers are always chasing that dragon, and these films are the ones that become classics.

In this regard, it's unusual how many of those films from the "golden age" of cinema managed to attain a perfect ending compared to all the movies being churned out today.

Orson Welles once said, "It's easy to make a good movie, but hard to make a great one." It just shows that even someone of his magnificent caliber can find it tough to achieve cinematic perfection. But it does happen from time to time!

Here are our picks for the best classic films that ended perfectly, and why those finales deserve to be called perfect.

7. Brief Encounter (1945)

The David Lean classic, which tells the tale of two married people who meet one afternoon at a train station before engaging in a romantic affair, is a movie that builds hope within the heart of the audience.

Laura and Alec's deep connection only swells with every meeting they have, as the film tells you that—while they know they're doing something wrong—they're caught in dreary marriages that have no fulfillment.

The film's finale comes when Alec and Laura spend their final day together, as Alex must move to South Africa with his wife. The couple is sitting at a table in the train station café, when their goodbye is ruined by a talkative familiar face who keeps chatting to them.

Alec's train is about to depart. He stands and touches Laura's shoulder with a gentle yet intense emotion. Then, he walks out the door and away from Laura forever.

Afterwards, Laura goes home and hugs her husband in an ending that leaves the audience conflicted yet deeply connected to the tragedy of Laura and Alec's ephemeral romance.

6. Casablanca (1942)

Arguably the most famous movie ending in history, Casablanca stars Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman as Rick and Ilsa, two former lovers who reunite in the city.

After a story that sees the pair fall back in love with one another—despite Ilsa now having a husband—they agree to leave Casablanca together to avoid the fast-approaching Nazis.

At the airfield, with everything in place, Rick suddenly switches the plan on Ilsa and forces her to leave with her husband. In their final moments together, Rick and Ilsa accept that they love one another but she must go with Victor because she's too important to his work with the Allies.

As the plane departs, with Rick and Captain Renault watching, Rick is protected from the police by Renault before the pair walk out into the mist, discussing their plans to go to Brazzaville together.

Rick and Ilsa's romance is the truest doomed romance of cinema, but their goodbye is a monument to the immediate perfection of the artform.

5. Citizen Kane (1941)

Orson Welles' masterpiece is a film that defined filmmaking as an artform in the 80 years since its release. Using several narrative techniques that were unheard of in the era, Welles showed us the death of Charles Foster Kane in the opening sequence before heading back to tell us his story.

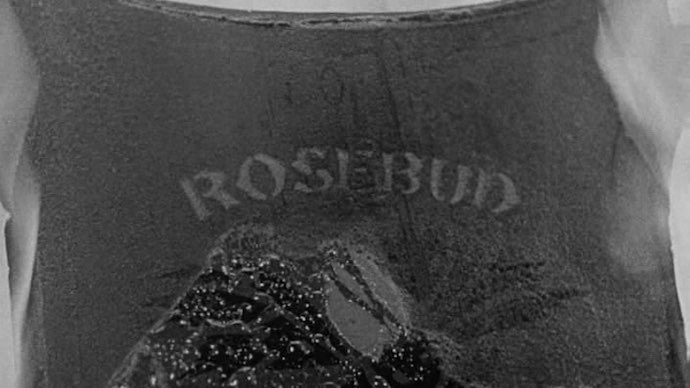

As we endure Kane's life, watching the tycoon as he descends into a lifestyle that brings him nothing but pain as a result of his constant miscalculations, his final word "Rosebud" haunts the film throughout.

When we finally reach the ending, and as Kane utters his final word before passing away, the meaning behind it becomes lost on the reporters who are trying to ascertain what it meant.

However, as Kane's possessions are sorted through and burned, his childhood sled "Rosebud" is thrown into the furnace. The true meaning behind the symbolic burning of Kane's final word is up to the viewer, but the intention behind Welles' filmmaking is genius.

4. City Lights (1931)

Charlie Chaplin's favorite of his own films, City Lights has an ending that hits the audience from nowhere, showing that the line between comedy and emotion is thinner than you'd think.

As The Tramp makes his way through the world, he decides to help out a blind flower girl by paying for her operation so she can see. The problem is, he has no money.

He manages to procure the funds throughout the film, but ends up incarcerated due to his actions. Months later, upon his release, he's poorer than ever—and he comes across the flower girl, who can now see and runs her new flower shop.

While he initially wishes to speak to her, The Tramp decides against it and walks away. But she senses that he's the person who paid for her surgery, and she's shocked to find that he's not rich as she had thought.

Smiling, they look at one another with a bond in their eyes never again replicated in cinema, giving the audience an ending that captures the essence of what it is to be human.

3. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

The tale of Jefferson Smith and his career as a US Senator leads to one of the best endurance sequences in the history of the big screen.

After being set up as a person who'd profit from his proposed bill, which makes Smith look guilty in front of the US Senate, Smith filibusters the floor of the Senate before they can reach the disciplinary vote that would see him removed from the Senate.

The filibuster sequence is something that the audience feels in their own legs after a while. Smith continues to stall the vote, hoping that he'll be exonerated by those who believe in him and his innocence, but his enemies know he'll only last so long.

However, as all hope appears to fade, Claude Raines' Senator Paine watches Smith collapse from exhaustion and finally breaks down—first trying to kill himself before telling the truth behind the rigged affair.

As far as cinematic fist-in-the-air moments go, the vindication of Jefferson Smith is a moment of pure delight for the audience as we see the good man is finally believed.

2. Roman Holiday (1953)

Roman Holiday is a romantic comedy that's a modern retelling of The Prince and the Pauper, Mark Twain's classic tale about a Prince who falls in love with a commoner.

When Princess Anne decides she's had enough of her Royal duties on a trip to Rome, she escapes the palace and heads out into the city while under the influence of a sedative.

In a sleepy haze, she meets Joe Bradley, a US reporter, who takes her in and gives her his sofa to sleep on for the night. The next day, Bradley realizes who she is and spends the day with Anne having fun around Rome, all the while gently falling in love.

However, she knows she must return to the palace and her duties, and she tells Bradley to drop her off at a street nearby. They share an emotional goodbye as she leaves without telling him who she is.

But, in the final scene, she meets the press as Princess Anne—and Joe Bradley is there, too. They exchange smiles and hidden messages in their words in front of the media, before Anne leaves the room. Joe then walks away, having lost somebody he loves in an ending that breaks the heart.

1. Tokyo Story (1953)

Tokyo Story follows two aging parents who take a long trip to Tokyo to see their children and grandchildren in their daily lives away from their home in western Japan.

As Shūkichi and Tomi stay with their family, they realize they're seen as an imposition rather than being heartily welcomed as they'd expected. So, Tomi decides to spend the evening with their daughter-in-law, Noriko, who's the wife of their deceased son.

Noriko, unlike the rest, seems happy to spend time with them. However, upon Shūkichi and Tomi's journey back home, Tomi falls ill and dies, leading the family to travel back home to comfort their father and see to their mother's possessions.

Once again, while the rest of the family has departed, Noriko stays and helps out her father-in-law. And before she leaves back to Tokyo for work, Shūkichi tells her that she's the only one who genuinely cared for Tomi during their trip, and that Tomi had spoken highly of her afterwards.

However, Noriko admits to not thinking about her dead husband as often as she should, believing herself to be selfish. Shūkichi tells her that she should move on and remarry, as he doesn't want to see her alone. He also gives her Tomi's watch as a sign of her place within the family.

The scene is perfect, emotional, and wholly engaging as Noriko's guilt is batted away by her father-in-law.