Most agree that cinema as an art form was birthed in 1895, when the Lumiére brothers screened their short films to a public audience.

Not only does that mean cinema has been around for more than a century, but that cinema has undergone so many evolutions with every movie director who's come and gone. These changes are often grouped together as "film movements."

From the very first silent films to the multilayered concepts of modern mumblecore, here are the most influential film movements that guided the trajectory of cinema over the decades.

15. French Impressionism (1910s–1920s)

French Impressionism refers to an avant-garde silent film movement that was born in France right after World War I. It had a huge influence on the future of Western cinema.

The main characteristic of this movement was its editing techniques, which focused on enhancing the aesthetic traits of every frame and portraying the character's psychological states.

Characters in French Impressionist movies were rarely positive and usually dark and troubled. Two classic examples from this era include The Wheel (1923) and The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928).

French Impressionism is the first movement to treat cinema as its own art form rather than a technique for recording plays on screen. Mood and psychological suggestions were at the foreground, pushing plot to the back and almost making it marginal.

14. German Expressionism (1910s–1930s)

Developed in tandem with French Impressionism, German Expressionism was also one of the most influential film movements to affect the future of Western cinema.

It had its roots in German Romanticism and portrayed the world in a unique way. Two emblematic works for this movement include The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Metropolis (1927).

After World War I, Germany embraced an air of despair and darkness, which manifested in their films. Further contributing to this process was the German government's banning of foreign films.

Often referred to as "the twilight of the German soul," German Expressionism basked in dark interiors and misty landscapes.

13. Soviet Montage (1910s–1930s)

Founded by Lev Kuleshov, Soviet Montage was born in Soviet Russia during the early 1910s. Two important films from this era include Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1927).

This film movement changed film editing worldwide by introducing one of the most iconic film techniques of all time: the montage!

Soviet Montage would intercut facial expressions with other images—often crude ones—in a way that was different from the romanticism and mystery that we saw in the previous two film movements.

It gave rise to what's now known as the "Kuleshov Effect," a phenomenon where more meaning is derived from two sequential images than from a single image alone.

In line with Soviet philosophy of the time, Soviet Montage films were mainly to educate people (and protagonists were often nameless).

12. Documentary Movement (1920s–1950s)

The Documentary Movement was tied to Great Britain's imperialist past. Pioneering documentarian John Grierson—amongst others—was interested in depicting the daily lives of specific slices of the population (down to specific ethnicities).

It was an endeavor that would be seen as insensitive today, but it was an important development for the documentary film genre. These pioneering documentary films paved the way for better ones.

The principle behind this film movement was to educate citizens, but with a very specific understanding of democratic society. Two iconic films from this era include Drifters (1929) and Song of Ceylon (1934).

11. Italian Neorealism (1940s–1950s)

What kinds of movies would you make if you lived under a fascist dictatorship and if you were there when the main Italian film studio of the time was bombed by the Allies?

For Italians, the result was Italian Neorealism. Born during Mussolini's reign, this film movement was all about portraying the reactionary, hardworking, starving side of Italy. Two iconic films to watch include Rome, Open City (1945) and Bicycle Thieves (1948).

This film movement depicted reality as it was, with individuals standing against many forms of evil. Its aesthetic manifesto involved long takes, amateur actors, and low-class characters living in ruins. It was mostly a self-portrayal of a thus-far misrepresented country.

10. The Polish School (1950s–1960s)

The Polish School film movement embodied the work of a close group of film graduates from Lodz Film School.

They alchemized their love for American and European films and used their skills to showcase the scars of war and repression. For all his faults, Roman Polanski was one among these filmmakers.

With a focus on psychology and identity, the Polish School film movement evolved into the beloved "Polish cinema of moral anxiety," made famous by Polish directors like Krzysztof Kieślowski, Krzysztof Zanussi, and Agnieszka Holland.

Two important films from the Polish School era of cinema include Ashes and Diamonds (1958) and Passenger (1963).

9. British New Wave (1950s–1960s)

Also known as the "Angry Young Men", the British New Wave film movement had a heavy emphasis on class division and urban life. These films were in reaction to the bombings and political struggles of the time. Two films to watch are Billy Liar (1963) and Darling (1965).

In later times, Ken Loch would partially take part in this movement—or at least the tail end of it—and invest in showing the other side of Britain, that the world didn't know about.

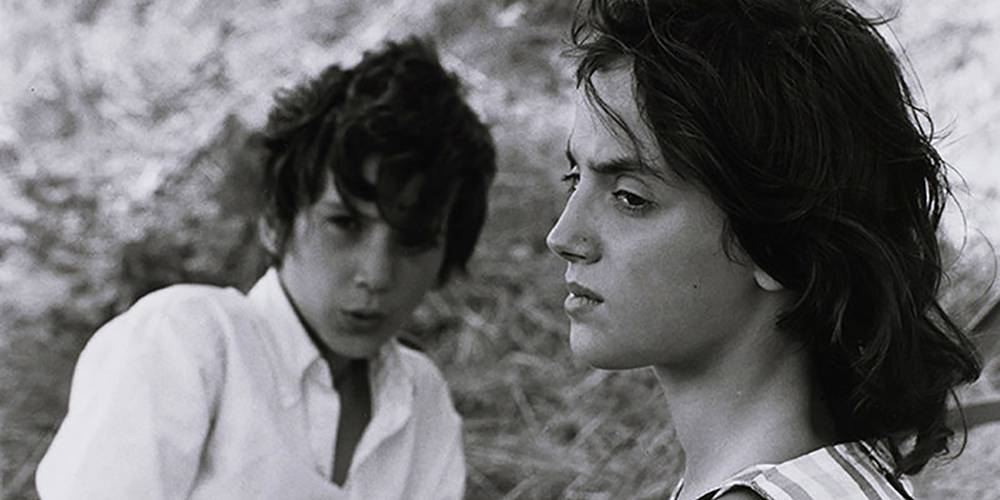

8. French New Wave (1950s–1960s)

Easily the most famous film movement of all time, the French New Wave is probably the answer you'd get if you asked anyone off the street to name the first film movement to come to mind.

Also known as the "Nouvelle Vague," this film movement was smart, experimental, fresh, and cheeky as it engaged with all kinds of themes the previous generation didn't want to talk about. Two key films to watch are The 400 Blows (1959) and Cléo From 5 to 7 (1962).

Characterized by jump cuts and nonlinear narratives, French New Wave filmmakers explored what it meant to tell a story, and they explored that in nearly every way imaginable.

It dove into a wider representation of young women, young men, teenagers, and children in a way that diverged from "how they should be." Additionally, the French New Wave gave us "auteur theory," which went on to influence cinema as a whole.

7. Cinema Novo (1960s–1970s)

Cinema Novo was inspired by the aforementioned Italian Neorealism, but this film movement was born and developed in Brazil.

It was a deeply reactionary movement that engaged with themes of social drama and political struggle, and it was marked by strong imagery and a fast-paced, almost chaotic editing style. Two films to watch are Black God, White Devil (1964) and Entranced Earth (1967).

Cinema Novo was one of the first attempts at Latin America's Third Cinema, focused on movies for poor and marginalized people and often self-described as an "aesthetic of hunger."

6. The Movie Brats (1960s–1980s)

The Movie Brats refers to the cinema movement spearheaded by Hollywood directors who didn't come from theater or television but instead learned about film through films.

We're talking about Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, John Milius, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg. Two iconic films from this era include Jaws (1975) and The Godfather (1972).

The style of this film movement was quite diverse, but they all shared in one thing: the tendency to pay tribute and homage to many other film movements of the past.

5. Iranian New Wave (1960s–1970s)

Iranian cinema experienced several waves throughout history, but the first Iranian New Wave may just be the most important.

The first Iranian New Wave started in 1964 as a reaction to popular cinema at the time, which failed to reflect how Iranian citizens truly lived and their real artistic tastes in society. It came to an end with the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

Two of the most important films from this movement include Where Is the Friend's House? (1987) and Madam Ahou's Husband (1968).

4. Dogme 95 (1990s–2000s)

Dogme 95 was an avant-garde filmmaking movement that was started in the 1990s by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg.

Through their manifesto, they developed a set of rules that were fundamental for them when creating movies: a foundation in story, acting, and theme while rejecting prominent use of special effects.

The content of these films were often disturbing as they engaged with all kinds of topics that were normally repressed, unspoken, or downplayed within Scandinavian society.

Two films to watch are The Celebration (1998) and Dogville (2003).

3. New Queer Cinema (1990s–2010s)

New Queer Cinema refers to a queer-themed film movement that started in the early 1990s and into the 2000s.

The term "queer" refers to the spectrum of human sexuality and gender identity, and these themes were at the forefront of this film movement to promote a different kind of queer representation in media.

New Queer Cinema developed into a more inclusive and experimental way of portraying queerness in film, which has since been folded into other cinema genres. Two iconic films of this movement include The Watermelon Woman (1996) and Rafiki (2018).

2. Greek Weird Wave (2000s–Present)

The Greek Weird Wave is one of the most complex and multilayered film movements since the turn of the millennium.

Awakened during the Great Recession that started in 2007, the movies of this movement are inherently postmodern. This film movement addresses taboo themes with political and social undertones, often through surreal, unsettling, and humorous ways.

With its fable-like vibe, the Greek Weird Wave engages with reality in a plethora of interesting ways. Two key films to watch are Dogtooth (2009) and Apples (2020).

1. Mumblecore (2000s–Present)

Mumblecore is a film movement that's thematically related to the more general term "indie film." Even so, there's more to the mumblecore film movement than just that.

With a predisposition for stories about people in their twenties, mumblecore movies look at life through lenses of naturalism and lost magic, with a focus on improvisation, low budget, and deep dialogue.

The mumblecore movement manifests the precarity of the lives of people who are entering their "real" adulthood. Two representative films to watch include Baghead (2008) and Frances Ha (2012).